THE 19TH AMENDMENT AT 100

How Women’s Suffrage Changed America Far Beyond

the Ballot Box

When the 19th Amendment was ratiied in August 1920, itlaunched a century of empowerment for

American women.

Reposted from original article at Wall Street Journal – Click here to view

By Ellen Carol DuBois

Updated July 31, 2020 1104 am ET

For American women, the battle for the right to vote was long and hard-fought, pitting

three generations of suffragists against the nation’s political and economic

establishment. When the vote was finally won, with the ratification of the 19th

Amendment in August 1920, many women looked forward to profound social change. The

activist Maud Younger thought she was about to witness “the dawn of women’s political

power in America.”

Others had more modest expectations. “I did not expect any revolution when women got

the ballot,” recalled labor leader Rose Schneiderman, who rose to fame with her speech

memorializing the victims of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in Manhattan. “But women

needed the vote because they needed protection through the laws. Not having the vote,

the lawmakers could ignore us.” Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the Black journalist and activist,

wished that her friends Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony “could have been here

to see the day when a woman’s ballot will count equally with a man’s.”

As we mark the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, it’s natural to ask if those

expectations have been met. What impact did the official entry of women into American

political life end up having on the country and on women themselves? What new

dimensions of the movement for women’s equality opened up once the franchise had been

secured?

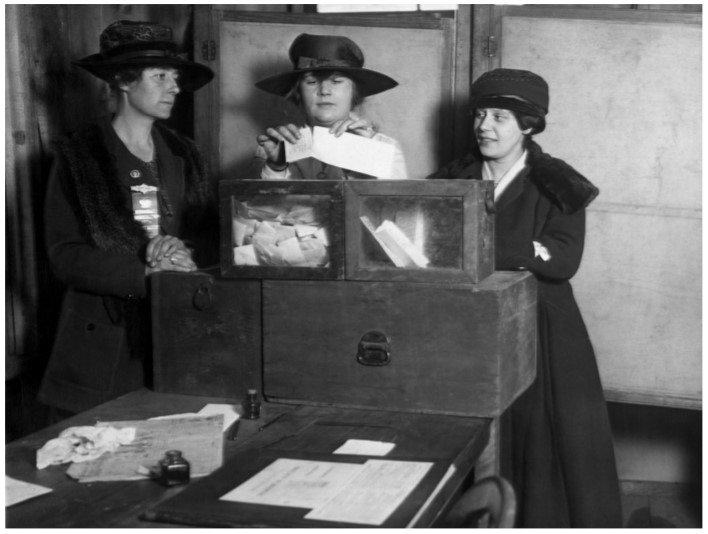

Suffragists cast votes in New York City, ca. 1917. PHOTO: EVERETT COLLECTION

In 1848, when the first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, N.Y., American

women were deprived of legal rights in virtually all dimensions of their lives. They were

excluded from higher education and most professions. The British common law principle

of coverture, carried over to the U.S., declared that in marriage, “husband and wife are

one and that one is the husband.” When a woman married she lost all control over her

finances. Any wages she earned went directly to her husband, and she couldn’t own

property under her own name. If her marriage dissolved, custody of the children

automatically went to her husband. Charlotte Woodward Pierce, 18 years old when she

attended the Seneca Falls Convention, was the only woman there who lived to see the

ratification of the 19th Amendment. She recalled that she didn’t think there was “any

community anywhere in which the souls of some women were not beating their wings in

rebellion.”

Meanwhile, one-tenth of the female population of the U.S. was brutally enslaved, suffering

endemic rape by their masters and powerless to stop their children from being sold away.

Two years after Seneca Falls, the first nationwide women’s rights convention issued a call

to “remember the two millions of slave women at the South, the most grossly wronged

and foully outraged of all women.”

Over the next three-quarters of a century, women made enormous gains in public life. By

1920, one-fifth of American women were working outside the home, approximately half of

them in the industrial sector, especially textile and garment production. The great

majority of Black women worked as domestic servants, but they were beginning to break

into factory work. Women had achieved significant standing in medicine, making up

about 10% of practicing physicians in major cities. Women had also become major figures

in American artistic and intellectual life. In 1921, Zona Gale was the first woman to receive

the Pulitzer Prize for drama, and two years later the Pulitzer Prize for poetry went to

Edna St. Vincent Millay. Both were advocates of suffrage.

Suffragist lead Alice Paul sews a star on a “Suffrage Flag,” ca. 1919.

PHOTO: EVERETT COLLECTION

Even before the 19th Amendment, American women wielded considerable influence in the

forging of social and economic policy. In 1911, Frances Perkins was appointed executive

secretary of New York State’s Commission on Safety, charged with reforming industrial

conditions after the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. She would rise to become Secretary of Labor

under Franklin Roosevelt—the first woman to hold a cabinet-level office. Social-work

pioneer Jane Addams created Hull House in Chicago in 1889; her example and her writing

would transform public attitudes toward social welfare and immigrant communities.

Women even made their way into the federal government, forming the U.S. Children’s

Bureau in 1912 to address appallingly high rates of infant and child mortality and the

scourge of child labor.

President Woodrow Wilson resisted a suffrage amendment for years, but in 1918 he was

forced to acknowledge that women’s contributions during World War I had earned them

the right to vote nationwide. As he told the Senate, the U.S. had fought for democracy, and

“democracy means that women shall play their part in affairs alongside men and upon an

equal footing with them.… Shall we admit them only to a partnership of sacrifice and

suffering and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

Upon the ratification of the 19th Amendment, approximately 30 million women became

voters, the largest expansion of the franchise in American history. But this didn’t mean

the end of the battle for equality. Although women could now vote, their entry into elected

office was extremely slow. In 1917 there was one woman in the House of Representatives,

Jeannette Rankin of Montana; by 1929 only eight more women had been elected to the

House and none to the Senate. “Now at the end of 10 years of suffrage, I find politics still a

male monopoly,” declared Emily Newell Blair, vice chair of the Democratic Party.

Women’s wages also lagged far behind men’s, and they were still confined to a limited

number of occupations and industries. To remedy this, the suffragist leader Alice Paul

proposed an Equal Rights Amendment. The first version, presented to Congress in 1923,

stated: “No political, civil or legal disabilities or inequalities on account of sex or on

account of marriage, unless applying equally to both sexes, shall exist within the United

States or any territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

Educator and civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune gives prizes to students, 1939.

PHOTO: AFRO AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS

In 1944, the wording of the ERA was simplified to read: “Equality of rights under the law

shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” By

assuming that the law only needed to protect an equality of rights that already existed,

this new wording weakened the amendment. The ERA continued to be submitted to

Congress annually, finally clearing Congress in 1973 but failing to win the needed

ratification by three-fourths of the states by 1982. Women were on both sides of that

hardfought battle, with conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly leading the successful

opposition.

When the 19th Amendment was passed, Black women, just two generations out of slavery,

eagerly sought to use their new rights to achieve progress for themselves and for their

race. Women who moved North with the Great Migration were able to vote in cities like

New York and Chicago with strong Republican parties. Even in the South, where the

majority of Black women lived, enfranchisement was energizing. In Nashville, Tenn.,

approximately 2,500 Black women voted in the 1920 election. In Florida, Mary McLeod

Bethune, the daughter of former slaves, worked through the National Association of

Colored Women to stand up to the Ku Klux Klan and protect the voting rights of Black

women. Eventually Bethune became the most politically powerful Black woman in the

country, a leader of Franklin Roosevelt’s unofficial “Black cabinet.”

Educator and civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune gives prizes to students, 1939.

Phyllis Schafly, a leading opponent of the Equal Rights Amendment, at a demonstration in Washington, D.C., in 1976.

After 1920, many of the activists in the suffrage army put their energies into other reform

efforts, including labor, international peace and civil rights. Two former suffragists, Jane

Addams and Emily Balch, became the second and third women to win the Nobel Peace

Prize, for their work in establishing the Women’s International League for Peace and

Freedom. Many suffragists were involved in creating the birth control movement, which

sought to extend women’s rights to freedom and equality from the public to the private

sphere.

Over the next half-century, the most fundamental changes for American women had less

to do with voting than with labor participation. By 1950, 29% of women were in paid

employment, and the rate continued to rise. Black women continued to move out of

domestic labor into factory and white-collar jobs.

Once women were no longer expected to choose between family responsibilities and work

outside the home, they had to learn to function in both arenas. By 1950, one-third of

working women were mothers of children under 18; today, the figure is more than 70%.

The challenge of balancing work and family became one of the defining struggles for

women in the late 20th century, leading to new campaigns for equal pay, accessible day

care and an equitable division of labor within the home.

The most recent movement for equality has focused on ending sexual harassment in the

workplace. Harassment had long been accepted as the inevitable cost of being a woman in

the male-dominated work world, but in the 1970s, women began to develop legal tools to

fight it as a form of discrimination, led by lawyers Catherine Mackinnon and Eleanor

Holmes Norton. In 2017, popular awareness over the issue exploded into the #MeToo

movement, which brought down a number of prominent and powerful men.

Since the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the battle over abortion rights has

been the most politically consequential women’s rights issue. Currently, 60% of women

consider themselves pro-abortion and 40% anti-abortion. The partisan divide on the issue

is stark: The pro-abortion position is embraced by three-quarters of female Democratic

voters, while two-thirds of Republican women are anti-abortion. Women of both parties

remain concerned with the impact of Supreme Court appointments on reproductive

rights.

Equal Rights Amendment supporters at the Democratic National Convention in 1980.

PHOTO: BILL PIERCE

Since 1980, when women voted for President Jimmy Carter over Ronald Reagan by an 8-

point margin, there has been a consistent “gender gap” in American politics, with

Democratic candidates doing better with women voters. According to a Pew Research

Center study of validated voters, in 2016 women preferred Hillary Clinton over Donald

Trump by a record 15-point margin.

But women don’t vote as a monolithic bloc. Black women voted 98% for Mrs. Clinton,

compared with 55% of white women. Education and age were also factors: Women under

50 voted 63% in favor of Mrs. Clinton, while voters of both sexes with a college education

picked Mrs. Clinton over Mr. Trump by 55% to 38%. Issues that motivated Democratic

women included the environment and treatment of racial minorities and LGBTQ people,

while Republican women were especially concerned about immigration.

Women officeholders have also made progress in the last 50 years. In 1994 the number of

women in the House jumped from 28 to 47, and in 2018 a record 102 women won House

seats—89 Democrats and 13 Republicans. At the age of 29, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of

New York became the youngest woman ever elected to Congress. Today, one quarter of

U.S. senators are women, the highest number ever, though still far below women’s share

of the population.

The other two branches of government also show the increasing significance of women. In

1981, Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman on the Supreme Court; today there are

three. Only the presidency, the highest glass ceiling, has so far remained stubbornly

closed to women (though in 2016, Mrs. Clinton outpolled Mr. Trump by almost three

million votes). In the 2020 presidential election, the Democratic primary field included six

women. Two women have been major-party nominees for Vice President, the Democrat

Geraldine Ferraro in 1984 and the Republican Sarah Palin in 2008; this year’s presumptive

Democratic nominee, Joe Biden, has pledged to name a female running mate.

Looking back at this history, it’s clear that the 19th Amendment wasn’t the end of a

movement but an extraordinary milestone in the ongoing fight to extend and protect

American democracy. A century later, women continue to stand in the forefront of the

The 19th Amendment wasn’t the end of a movement but an

extraordinary milestone in the ongoing fight to extend and

protect American democracy.

In an effort to protect Americans’ democratic rights and to achieve greater diversity in our

political leadership. They can take inspiration from the campaigners who, in the words of

suffragist leader Carrie Chapman Catt in 1920, “kept the flying flag of the principles of the

Declaration of Independence, the principles of the Constitution, and have educated the

public in those principles.”

Dr. DuBois is a professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the

author of “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote,” published by Simon & Schuster