To view LA Time FULL ARTICLE click here.

One hundred years ago Tuesday, Tennessee became the 36th and final state needed to ratify the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote across the United States. In California, that right was already enshrined in law in large part thanks to the efforts of women in Los Angeles.

Katherine Edson was one of them. A middle-class mother of three, she came to the suffrage movement through a campaign for enforceable pure milk laws. “If the milk supply is in the hands of politicians,” she argued, “how can a woman who wants to do the right thing by her babies keep quiet while they drink impure milk?”

When California Progressives won control of the state Republican party in 1910, Edson led a delegation of Los Angeles women to convince them to put a state constitutional amendment enfranchising women on the ballot for October 1911. Suffrage supporters had just nine months to organize.

Although Los Angeles promoted itself as a proudly white, middle-class city, it never really was, and its suffragists knew they would need a diverse coalition. A substantial minority of the city at that time was Mexican or of Mexican descent, including Maria de Lopez, whose family had come to the San Gabriel Valley in 1849.

Suffrage League and went on to become an instructor at UCLA. She saw to it that suffrage leaflets were translated into Spanish, 50,000 of which were distributed by election day. She gave speeches from Ventura to Pasadena in both English and Spanish and, a week before the election, she drew a crowd of thousands at a rally in Los Angeles Plaza.

Women’s suffrage, she believed, “was the most momentous question that has ever come before the people of this coast.” Without women, she asked rhetorically, “can we have a democracy?”

Frances Nacke Noel, a German immigrant and socialist, made it her mission to organize the city’s working class. Her organization, the Wage Earners Suffrage League, brought working-class women into a coalition with Edson’s middle-class women. The campaign, she declared the month before the election, has broken “down the social barriers which so cruelly separated the interests of women.”

The Los Angeles suffrage coalition developed a wide range of innovative tactics. To get around an anti-labor ordinance prohibiting public meetings, they organized a suffrage “picnic” where they distributed “votes for women” doughnuts. Sixty-three-year-old Clara Shortridge Foltz, the state’s first female lawyer, whose name graces the county criminal courts building in downtown L.A., went up in a hot air balloon to scatter leaflets printed on “suffrage yellow” paper.

Middle-class women who owned automobiles drove out to small towns to preach suffrage from town squares. In the San Joaquin Valley, one man who heard Edson was so thrilled by her speech that he told a reporter, “If that woman was my wife, she could vote or do anything she wanted!”

But L.A.’s suffragists also faced fierce opposition. The Los Angeles Times ran attacks on their campaign, and the city’s powerful railroad interests went on the attack, fearing that women would vote to implement more government regulations. The chairman of the state Democratic Party called women’s suffrage a “disease,” advocated by the “mannish female politician and the little effeminate, sissy man.” Two days before the election, the Southern California Assn. Opposed to Woman Suffrage published a manifesto in The Times. “The vast majority of California women do not want to vote,” it asserted. “The woman suffrage movement is a backward step in civilization.”

Los Angeles suffragists did not let up. “Do not lull yourself into the belief that the vote has been won,” Edson told the city’s suffragists on the eve of the election, urging them to “begin early and work late” on election day. In a massive get out the vote effort, they drove voters to polls across the city in an estimated 260 automobiles. “Mothers take your sons. Girls take your sweethearts, your brothers or your fathers,” they urged. Prohibited from getting within 120 feet of polling places or talking to voters, they stood in silent phalanxes, holding up posters that called for a “square deal” for women.

Early returns suggested the measure would be defeated. But as more distant electoral districts reported, the yes side began pulling ahead. Two days after the vote, headlines announced that the suffrage amendment had eked out the narrowest of victories, winning with a margin of 3,800 votes out of 246,000 cast, or about 1.5%. The voters of Los Angeles were largely responsible for the win, voting 27,400 to 22,200 in favor, offsetting anti-suffrage votes in San Francisco and Alameda counties.

Newly enfranchised, California women immediately advanced a series of state measures promoting a minimum wage and maximum hours for working women, as well as support for single mothers and teachers’ pensions. Progressive legislators, still in control of the state Republican Party, passed the majority of their bills.

Meanwhile, national suffrage leaders realized that the votes of women in California and, by 1914, 11 other suffrage states could be a powerful lever in the campaign to win a national constitutional amendment. In January 1918, the House of Representatives narrowly passed a suffrage amendment. Passage in the Senate took another grueling 18 months, after which it was up to states to ratify the amendment. That took another 14 months, with suffragists waging campaigns across the nation, undeterred even by a third wave of the influenza pandemic.

In November 1919, the California legislature, with virtually no debate and voting almost unanimously, became the 18th state to ratify. Nine months later, the Nineteenth Amendment allowed more than 20 million women to join those of California and other suffrage states to become full-fledged American voters.

Ellen DuBois is a professor of history and gender studies at UCLA and the author, most recently, of “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote.”

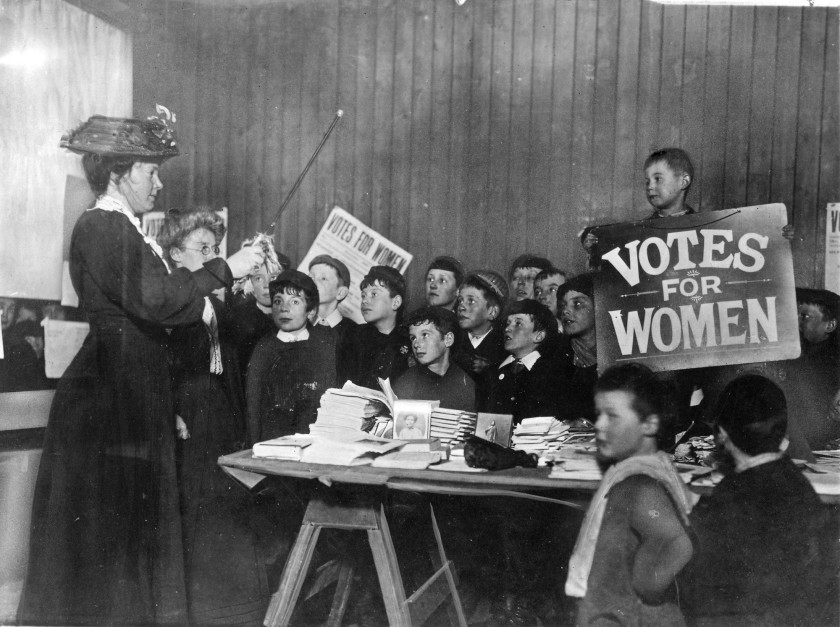

PHOTO CREDIT: School children learn the suffragist “war song.”