To watch the VIDEO click on the link below:

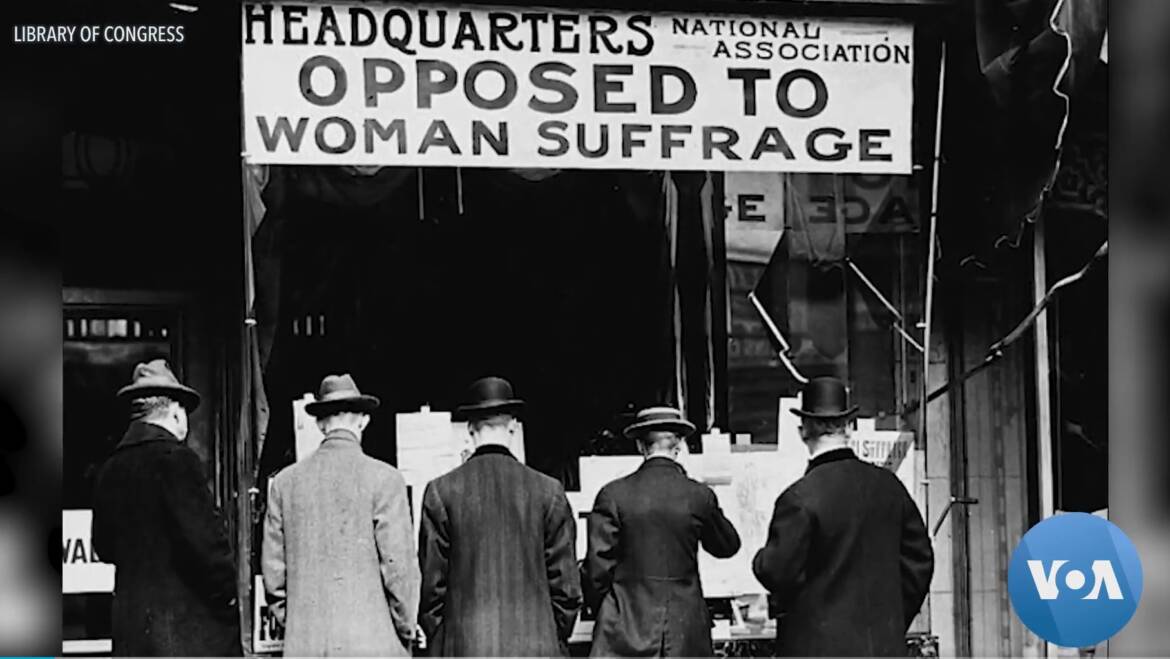

WASHINGTON – Feminists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries fervently campaigned for women’s suffrage in the United States by organizing, petitioning and picketing.

One hundred years ago this month they were finally granted the right to vote through passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

From the time the amendment was introduced to Congress in 1878, it took more than 40 years for it to be passed and then ratified by three-quarters of the states.

The fight to vote goes back to the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. Held at Weslyan Methodist Church, the convention was attended by an estimated 300 people, including abolitionist Frederick Douglass. No women of color were present.

The church is now part of the Women’s Rights National Historic Park in Seneca Falls, which commemorates the birthplace of the women’s rights movement.

Delegates included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the principle author of the Declaration of Sentiments, a document written at the convention calling for equality with men, including the right to vote.

Andrea DeKoter, the park’s acting superintendent, told VOA the Declaration of Sentiments is modeled after the U.S. Declaration of Independence. But the words — “all men are created equal” — were changed to, “all men and women are created equal.”

DeKoter points out that only African American men were granted voting rights in 1870 through adoption of the 15th Amendment. But as women fought for their own suffrage, there was “a huge schism and racism in the women’s rights movement” because white suffragists excluded Black women, DeKoter said.

“So, in the course of two centuries, Black women form a parallel movement within their own organizations,” said Martha S. Jones, a history professor at Johns Hopkins University and author of “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.” Jones said these included “church conferences, civil rights organizations and antislavery societies.”

Some states had passed their own women’s suffrage legislation, but women’s rights activists wanted a national amendment that said “The rights of citizens of the United States will not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex.”

New activists

As the roles of women were changing in the early 20th century, a new generation of young, determined women continued the struggle.

“They were college graduates and a quarter of the labor force,” said Ellen Carol DuBois, a historian of women’s suffrage and author of “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote.”

“They were prize-winning writers, poets and artists,” DuBois added.

By 1916, these suffragists stepped up their protests — organizing parades, silent vigils and hunger strikes. They were harassed and jeered.

“They give speeches for women’s suffrage in public to rally male audiences and go into crowds of men at factory gates at lunchtime, and they often win them over,” DuBois said.

Renewed momentum, along with President Woodrow Wilson changing his stance and supporting the amendment in 1918, eventually led to its passage two years later.

A century later, many women still face voter suppression, says the League of Women Voters, including “forcing discriminatory voter ID and proof-of citizenship restrictions on eligible voters, reducing polling place hours in communities of color, and illegally purging voters from the rolls.”

Inequalities like these and others may be alleviated through passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, proponents say, which was introduced to Congress in 1923, three years after women gained voting rights. The ERA was approved by the House of Representatives in 1971 and by the Senate in 1972. It was ratified by three-quarters of the states in January 2020 — years after the deadline.

Eleanor Smeal, president of the Feminist Majority Foundation, argues that if the deadline was removed, the amendment that says “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex,” could become a part of the Constitution.

Like women who fought for voting rights, Smeal said, “the Equal Rights Amendment is very important because it establishes that all women must be treated equally under our Constitution.”

Among other things, she explains, it will end pay, education and insurance discrimination, and help prevent violence against women.